Share and Follow

Legend has it that on February 2nd, if a groundhog sees its shadow, we can expect six more weeks of winter, while the absence of a shadow suggests an early spring. However, these furry creatures, also known as woodchucks, are not emerging from their burrows solely as weather forecasters. The biology of groundhogs indicates they have more pressing matters than simply mingling with the residents of Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania during this time.

The origins of Groundhog Day can be traced back to Europe. Early February, nestled between the winter solstice and the spring equinox, has historically been a time for celebration. The ancient Greeks and Romans held mid-season festivals around February 5th to herald the approach of spring. In the Celtic tradition, this period was marked by the festival of Imbolc, which celebrated the beginning of spring. This tradition was later adopted by early Christians in Europe, who celebrated Candlemas Day on February 2nd to honor the purification of the Virgin Mary. On this day, candles were blessed and distributed to light the way through the remaining winter days in anticipation of the warmer season.

It’s Groundhog Day!

In northern Europe, farmers sought signs to determine the right time for spring planting. They looked to the emergence of hibernating animals like hedgehogs or badgers as indicators of spring’s arrival. These animals typically emerged in early February, leading to the belief that a sunny Candlemas Day, when the hibernator saw its shadow, foretold more winter weather, whereas rain or snow indicated a mild remainder of the season.

This tradition made its way to America with German immigrants who settled in eastern Pennsylvania. Upon discovering an abundance of groundhogs in the area, they adopted this native creature as a stand-in for the hibernators of their homeland, thus continuing the tradition in the New World.

This tradition was brought to America by the Germans who migrated to eastern Pennsylvania. They found groundhogs in profusion in many parts of the state and decided this mammal was a perfect replacement for the hibernators they’d left behind in Europe. Thus, the tradition continued in America.

Hibernation helps survival

In my study area in southeastern Pennsylvania, the average date groundhogs emerge from their burrows is February 4. This fits the folklore and the timing of Groundhog Day. However, predicting the weather is not their objective.

The real reason is related to Darwinian fitness – a measure of an organism’s ability to contribute its genes to the next generation. The process defines natural selection and is based on an organism’s ability to survive and to reproduce successfully. High Darwinian fitness suggests an individual will pass on its genes to many healthy offspring.

Hibernation contributes to Darwinian fitness value. It enhances survival by saving energy during times of limited food availability. The ability to hibernate is found in several mammalian groups, including all marmots, many species of ground squirrels, chipmunks, hamsters, badgers, lemurs, bats and even some marsupials and echidnas. Curled up in their burrows, they pass the winter months, when food would be hard to come by.

Hibernation: alternating torpor and arousal

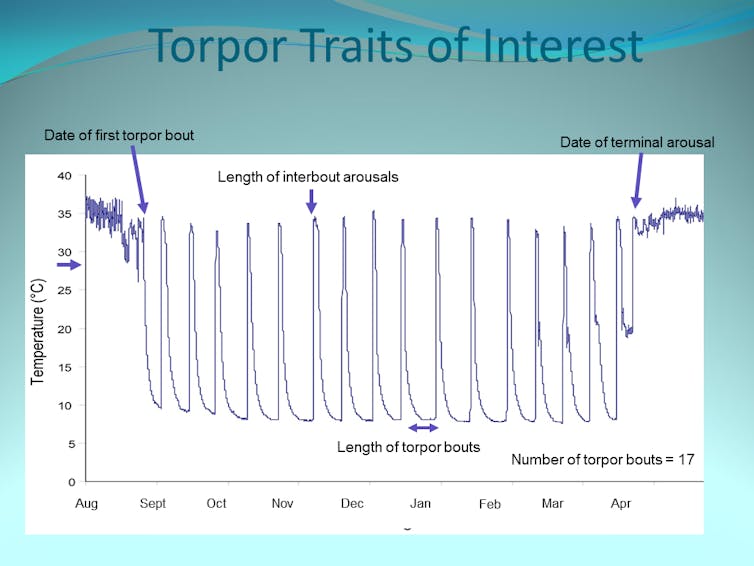

Hibernation is characterized by a significant drop in body temperature and metabolic function. This process is commonly called torpor. During torpor, body functions including heart rate, breathing rate, and brain activity are reduced. The overall benefit for the animal is saving metabolic energy at a time when it isn’t eating.

However, for some still unexplained reason, hibernators arouse periodically during their hibernating season. These arousals come at a great energy cost. Therefore, arousing must be critical to survival in some way or animals wouldn’t waste the energy on it. Some possibilities include maintaining cellular functions or disposing of bodily wastes.

In Pennsylvania, these bouts of torpor and arousal continue throughout the hibernation season, starting on average in mid-November and ending by the beginning of March; a total of about 110 days. In one study, an average of 15 bouts of torpor occurred during this period, with arousals in between. Groundhogs aroused for about 41 hours and then returned to torpor for about 128 hours for males and 153 hours for females.

In a 2010 study, we determined that the hibernation periods for groundhogs increase in length with increasing latitude. The hibernation period matches winter’s duration. The celebration of Groundhog Day would need to change by latitude in order to perfectly match groundhog emergence.

It all boils down to sex

One of the drawbacks of hibernation is the reduced time available for reproduction. Thus, hibernators have developed mating strategies to maximize reproductive success. Groundhog mating strategies involve temporary emergence in early February, mating in early March during during their final arousal, and giving birth in early April. This behavior enhances reproductive success because young are born as early as possible (but not too early) and are able to start feeding in May when lots of food is available. That way they have enough time to gain sufficient weight to survive their first winter hibernation.

But why do groundhogs emerge in February, when mating won’t occur until next month? The answer lies in their social structure. Most of the year, male and female groundhogs are solitary and antagonistic against each other. They aggressively maintain a feeding territory around their burrows and rarely have any contact with each other. February is used to reestablish the bonds necessary for mating and ensures that mating can then proceed without delay in early March.

So for the animals themselves, Groundhog Day is more like Valentine’s Day. On February 2nd, groundhogs don’t emerge to predict the weather, but to predict whether their own mating season will be a success!