Share and Follow

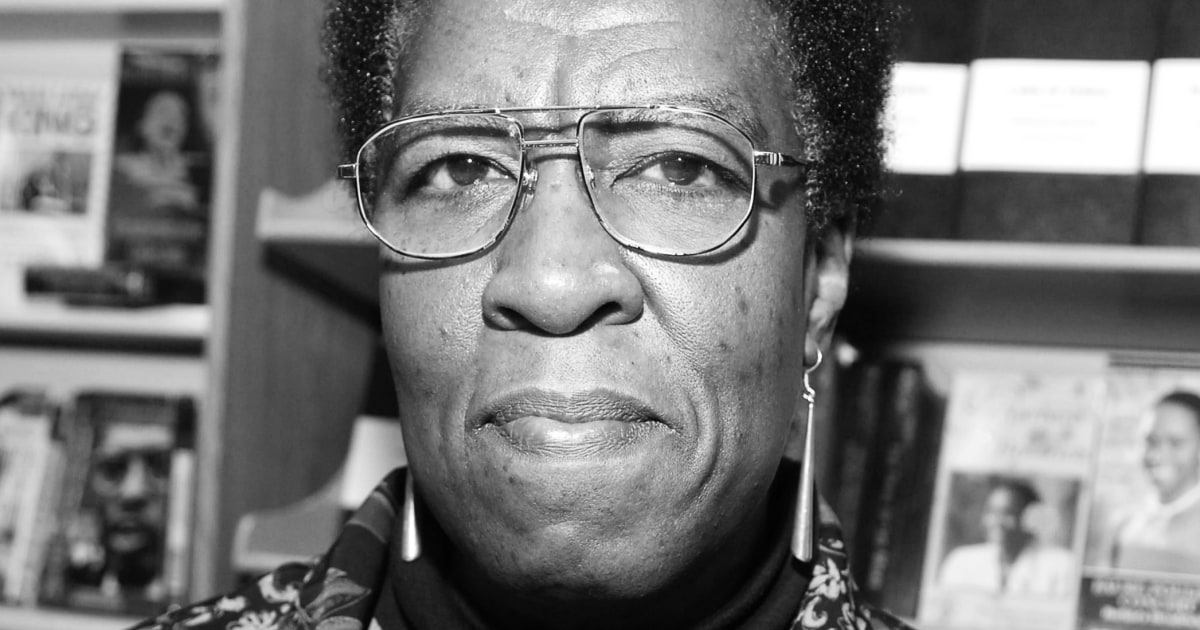

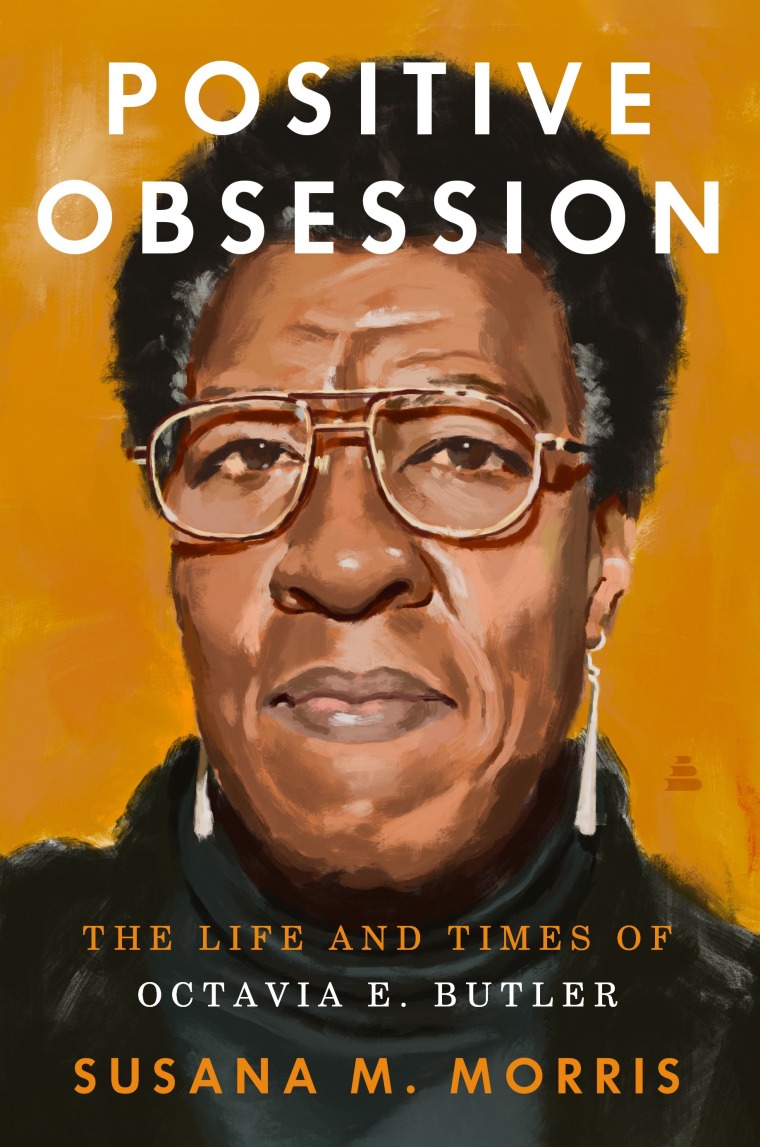

For pioneering science fiction novelist Octavia E. Butler, writing was more than a profession. It was a form of survival, resistance and reflection. In “Positive Obsession: The Life and Times of Octavia E. Butler,” author and college professor Susana M. Morris shares the quiet yet radical story of Butler’s life, revealing how the worlds she imagined were shaped by the one that often shut her out.

Going from a shy Black girl, born in 1947 and raised under Jim Crow, to a literary icon, Butler’s path to success was not linear. She was told not to dream but to get a “real” job. As she juggled temp jobs, financial anxiety and a society that resisted making room for her, Butler wrote genre-defining literature that has been adapted for TV and film in recent years, and has continued to go viral nearly two decades after her death in 2006 at 58.

“Positive Obsession,” named for a 1989 essay by Butler, pulls from journals, interviews and personal letters in Butler’s public archives to illuminate the forces that shaped her, revealing an ambitious and meticulous writer.

For most of her career, Butler woke up before dawn to write for hours ahead of what she once called “lots of horrible little jobs.” As she toiled in factories and warehouses, washing dishes, inspecting potato chips and making telemarketing calls, Butler conjured characters from her everyday encounters.

Morris told NBC that in sharing Butler’s story now, 19 years after her death, she hopes to inspire artists who don’t think they can afford to create to find the time.

“In this economic system that we’re currently in, we are so crunched down trying to buy eggs or pay the rent,” Morris said “sometimes we don’t even feel like we can access art for art’s sake. But through all the trials and tribulations, she was accessing it.”

Butler’s journals show how writing was her way of pushing back against racism, patriarchy and other norms that frustrated her and made her feel overlooked as a creative person and a public intellectual. She wrote because “she had to,” Morris writes. She put pen to paper to make sense of the world and speak back to it.

Beyond writing novels, Butler eventually became known for her direct and evocative engagement with readers, whom she pushed to think deeply about the world around them. She analyzed real-world dynamics and extrapolated them into prescient and cautionary fiction. She wrote stories that seem to have become only more popular as time has passed. Her novel “Kindred” was reimagined into a TV series in 2022, and authors John Jennings and Damian Duffy won a Hugo Award in 2021 for their graphic novel reimagining of her book “Parable of the Sower.”

On social media, the “#OctaviaKnew” trend captures the ominous ways her words resonate in the present on issues like climate change, inequality and politics. Her ability, decades ago, to conjure how we live now gives Morris’ students a feeling of connection to Butler’s work today.

In “Parable of the Talents,” published in 1998 and set in the 2020s, Butler introduces a conservative presidential candidate who urges voters to join him in a project to “make America great again.” The words on the page reverberated through Morris’ classroom as she taught the book during Trump’s first presidency. It’s why many readers think Butler’s work was nearly prophetic. “Psychic? Maybe not,” Morris says. “Prescient? Absolutely.”

Morris uses the 1987 short story “The Evening and the Morning and the Night” — about a community grappling with a fictional genetic disorder — to talk to students about the marginalization of people with disabilities.

Butler’s 1984 short story “Bloodchild” pushes readers to rethink gender, reproduction and family. “We’re living in a moment that demonizes transness,” Morris said. “But in ‘Bloodchild,’ men carry the babies. It complicates our idea of what bodies are supposed to do.”

Butler’s fiction never floated away from reality. It confronted it. And it continues to make readers question what they thought they understood. Though often shelved as science fiction, Morris says Butler’s work transcends the label, and she instead classifies it as “speculative fiction.”

Morris’ immersive portrait can at times feel like reading Butler’s journal or listening to the innermost thoughts of a quiet and sometimes lonely person.

“She lived a life of the mind,” Morris said. Out of that life came work shaped by discipline, imagination and a kind of beautiful obsession — one that Morris hopes others might mirror in their own lives.

“I hope that in this world that is often devoid of beauty,” Morris said, “that other folks can see her example and find the beauty in their own kind of practice.”