This story contains references to and images of an Aboriginal person who has died and distressing elements, including references to suicide, self-harm and offensive language.

A woman leans on the shoulder of a support worker sitting beside her. There’s the sound of sniffling and she starts wiping away tears.

She is sitting in the NSW Coroners Court and has just been shown CCTV footage of the moment her brother Tian Jarrah Denniss placed a blanket over the camera of his prison cell before he took his own life.

Denniss died by suicide despite being housed in a specialist unit for offenders at high risk of self-harm.

From the public gallery, it’s almost impossible to see the vision of his cell — it’s a small box among rows and rows of screens displayed on a large wall, which two correctional officers were expected to monitor as part of their duties.

The footage strips away any doubt about how quickly prison staff acted and provides sobering answers to questions posed by the counsel assisting the coroner.

How long did it take for the guard to notice that Denniss’s cell camera had been covered and to act? At least five minutes.

How long before a guard was at his door? Up to 12 minutes.

How much longer before first aid was delivered? Another seven minutes.

In total, it took at least 24 minutes for someone to enter Denniss’s cell and provide assistance.

Over the course of two and a half weeks, the court will see and hear the moments leading up to the end of Denniss’s life, and the decisions that could have made a difference.

There are tears from one of the guards involved, who admits he should have done more.

Iesha Murphy, Denniss’s sister, says seeing separate CCTV footage of four guards standing outside her brother’s cell — at one point laughing and sharing a joke that none of them can now remember — was the moment that stuck with her the most.

“No one opened the cell door,” she says.

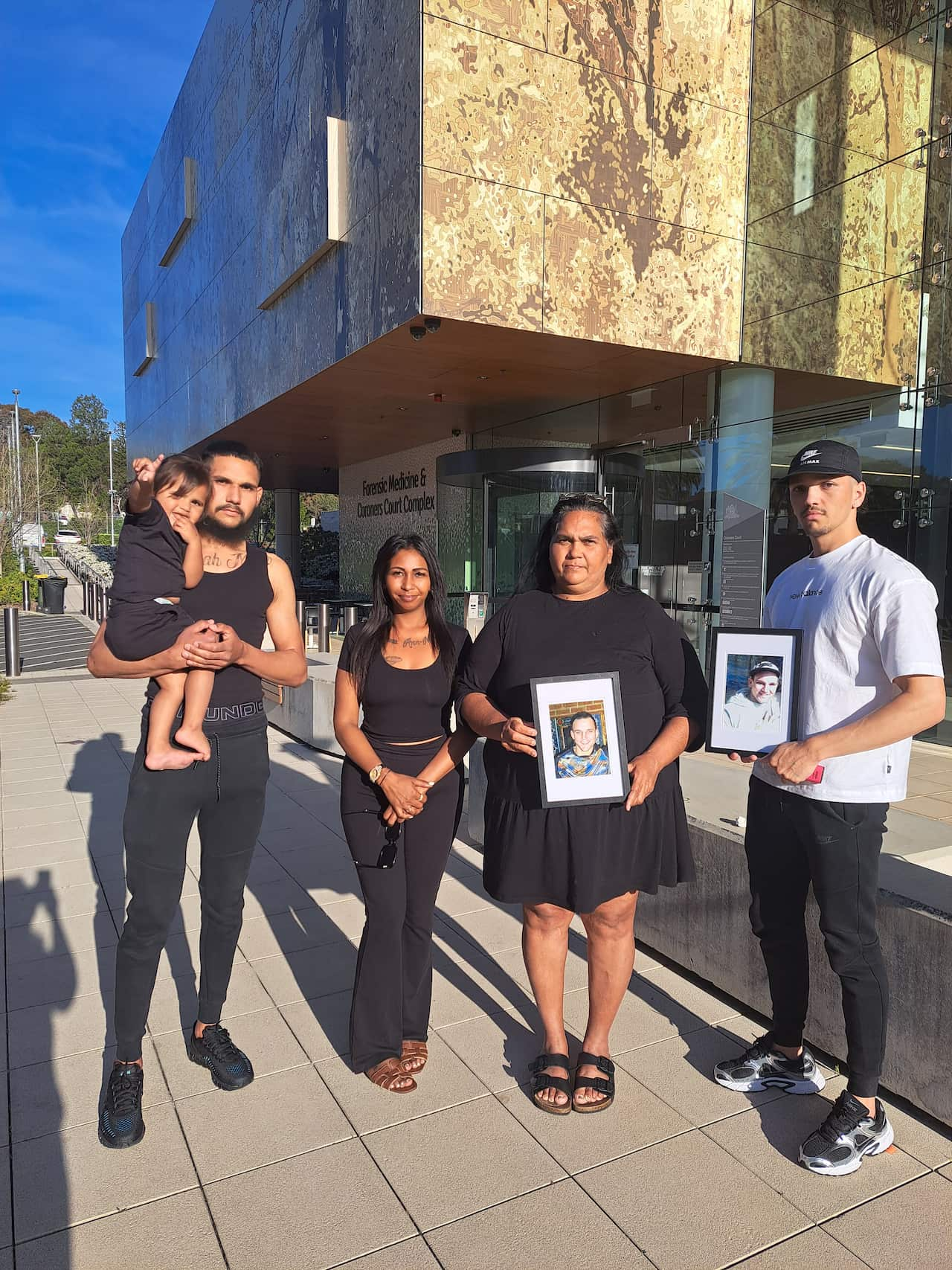

(Left to right): Tian Jarrah Murphy’s brother Brayden (holding daughter Amyah), sister Iesha Murphy, stepmum Charlene Murphy and cousin Shane Williams, holding photos of TJ that sat in the court during the inquest into his death. Source: SBS News

The coronial inquest into Denniss’s death in custody raises questions around the adequacy of Corrective Services NSW’s treatment of at-risk inmates, particularly those like Denniss, who have underlying mental health conditions — representative of around half of Australia’s prison population.

According to the National Prisoner Health Data Collection 2022, 51 per cent of adults entering prison reported being told they had a mental health or behavioural condition (including drug and alcohol abuse) at some point in their lives.

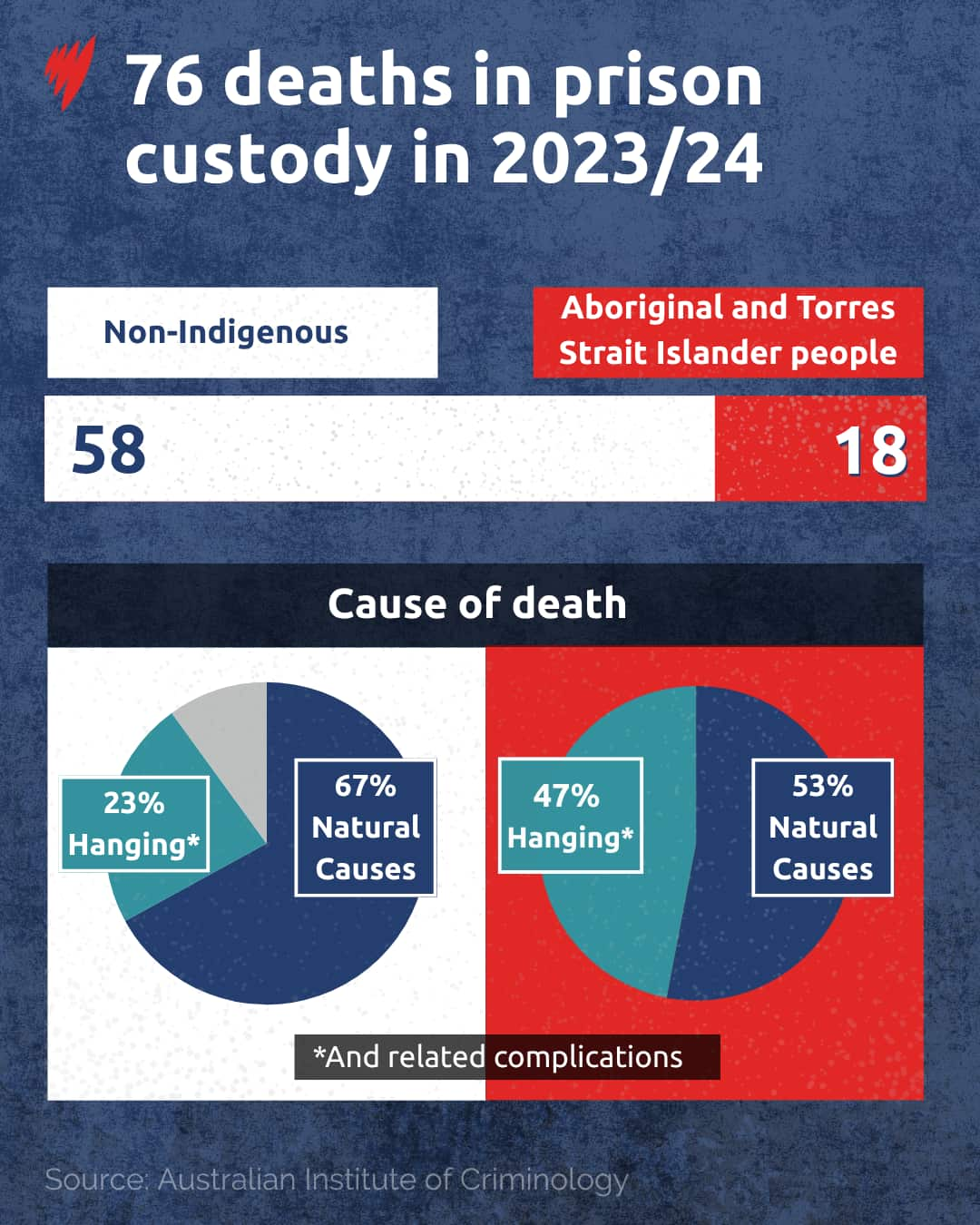

In 2023/24, there were 76 deaths in prison custody — 25 per cent of which were attributed to hanging and related complications.

It raises the question: Are those tasked with keeping inmates physically safe actually able to fulfil their duty of care, especially when staff are not adequately trained to recognise or handle those in psychological distress?

And how can inmates be helped to address trauma and improve their mental health so that they move beyond cycles of offending and imprisonment?

To find out, SBS News attended the inquest into Denniss’s death last month, which revealed numerous failures by authorities on the night he died. This is how it unfolded.

TJ had a ‘cruel’ life

The Coroners Court in the western Sydney suburb of Lidcombe is a light-filled building with large windows overlooking a busy highway. It’s surrounded by wide palm tree-lined residential streets, and its proximity to Rookwood Cemetery acts as an uncomfortable reminder of why we’re here.

The solemn and focused atmosphere of the courtroom, where two framed photos of Denniss sit on either side of Coroner Teresa O’Sullivan, is broken only by the spirited appearance towards the end of the inquiry of several of Denniss’s young nieces and nephews, who wriggle around on their seats until escape proves irresistible and they scamper out the door.

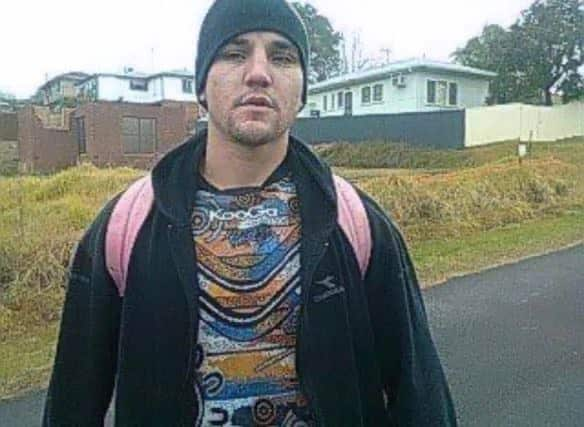

Tian Jarrah Denniss was considered a “challenging” inmate but his family say he was a nice person who struggled to get free of the justice system. Source: Supplied

Most of the time, the children don’t seem to understand the gravity of the event they are attending, but one of the older girls leaves the courtroom crying on the inquest’s final day as heartfelt family statements are read out.

Denniss, who was 33 at the time of his death, had been in and out of prison since he was a teen — a place where he was considered “challenging” and at times dangerous. To his family, he was a person who was loved and would be missed.

His sister Iesha Murphy says Denniss, whom the family called TJ, didn’t have the best life — “some would say it was cruel” — but he would have wanted people to know what happened to him. His stepmum Charlene Murphy agrees.

“He always stuck up for other inmates even though sometimes harm [came] to him,” Charlene tells SBS News outside the court.

“That’s just the person he was, and that’s the person we will remember.”

Officers ignored TJ’s calls

Minutes before Denniss died by suicide in a NSW prison cell on 5 August 2023, he made one final call to the officers responsible for his care.

A correctional officer in the monitoring room answers the call at 6.53pm. Denniss tells her he intends to self-harm and pleads with her to do her job.

She replies exasperatedly: “Oh, will you stop threatening me?”

Denniss had already attempted two separate acts of self-harm around 2.20pm and 5.30pm that day, and had been using the knock-up system — which is only supposed to be used for medical emergencies — to make several calls.

His calls were considered an “abuse” of the system, but guards admitted there was no other way for him to request items he was entitled to — such as playing cards or crayons — other than calling out to guards as they passed by.

Recordings played at the inquest reveal the woman receiving Denniss’s distress calls had earlier told him to “f— off”, calling him an “idiot” and “f—ing dog” after he kept ringing.

The officer, who admitted to watching TV while on duty that day, told the inquest she shouldn’t have sworn at Denniss and that it was unprofessional, but it was common for staff and prisoners to swear at each other.

Shortly after his final call, CCTV shows the woman phoning the two guards stationed in the pod office near Denniss’s cell to tell them he had covered the camera monitoring his cell. They should then have gone to check on him immediately, but they didn’t.

Denniss had days earlier been placed in what’s known as the complex placement unit (CPU) at the Metropolitan Remand and Reception Centre — a maximum-security facility at Sydney’s Silverwater Correctional Complex. His cell had a transparent door and surveillance camera, intended for visibility and close monitoring of inmates deemed at high risk of self-harm.

The CPU had only been set up a few weeks earlier and no specific model of care had been put in place. It’s also unclear what behavioural progress inmates needed to make to be discharged from the unit.

Silverwater Correctional Complex in Sydney. Source: AAP / Dean Lewins

Two guards on duty had been instructed to check on Denniss every half hour but they had not been to his cell door since 5.30pm and had also been ignoring his calls, deferring instead to the monitoring room.

They were asked by the monitoring room to check on Denniss just after 6:53pm, but the guards waited until 7pm.

Footage at 6.56pm shows the two men still seated: One is swivelling around on his office chair, while a football game plays on a TV in the office.

By 7.07pm — 14 minutes after receiving the alert from the monitoring room — officers finally entered Denniss’s cell to deliver first aid, but he could not be revived.

‘Playing possum’ to get coffee

For inmates in segregation in the CPU, afternoons can be a lonely and boring period. Dinner is served around 2pm and inmates are locked in their cells for the night by around 3pm.

There’s no roommate to talk to, no TV, and no food, tea or coffee until breakfast at seven the next morning.

Unlike other inmates, those in the CPU are not entitled to purchase ‘buy-ups’ — convenience food such as instant noodles and other goods they can eat when they want — due to the risk of self-harm.

Denniss had arrived at the facility six days before his death, and there’s no evidence he had been allowed out of his cell during that time.

It’s not clear whether he had been given colouring books, crayons or playing cards to help pass the time.

Tian Jarrah Denniss died in NSW prison custody in 2023. Source: Supplied

One of the two officers working on 5 August 2023 told the inquest it was his first shift monitoring the CPU. While he had worked in other areas of Corrective Services NSW for eight years, he said he had not received specific training regarding the treatment of inmates in the unit or how to assess their mental health, and despite having read the inmate’s management plan, he fell back on what he thought was general practice, and did not have a good grasp of official procedures — which were also contradictory at times.

He told the inquest he believed there should be no contact with inmates during the evening shift, known as C watch, because they could be challenging to deal with, even though this was not reflected in prison policies. He said he did physical observations from his chair in the office, where he could see Denniss’s cell, instead of walking to his door.

“If you [are] continuously interacting with them, that’s the time they manipulate you,” he told the inquest.

Denniss was known among prison staff for “playing possum” — faking injury to get attention from the guards.

The other officer on duty in the CPU that night recalled Denniss would often pretend to hurt himself so he could ask for food or cups of coffee when the officer arrived at his cell.

However, when asked whether he had gone to Denniss’s cell that day to check on him — apart from when he had threatened suicide — the officer said “no”.

The counsel assisting, Kirsten Edwards SC, pointed out that the two officers were watching TV while Denniss was calling for help, and were not busy.

“Yes,” one of the guards said in response.

A challenging inmate

Denniss’s sister Iesha Murphy told the court her brother, who was born in Wagga Wagga in country NSW, was “constantly on the go”. He loved being outdoors and playing sports such as soccer, and would teach his cousins how to dance, ride bikes and rollerblade.

He had been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a young person and was mostly homeschooled — in part due to bullying at school — but the court heard he was proud to help his cousins with maths and spelling homework.

He would often invite strangers home for a feed and a shower, sending them off with bags of instant noodles and tea.

However, Denniss’s childhood was marred by “trauma”. The term is repeatedly mentioned during the inquest; peppered throughout proceedings, along with other details, such as Denniss’s Indigenous heritage.

His family are reluctant to speak directly about his childhood experiences, but an ACT court judgment from 2018 notes that Denniss had a “deprived and dysfunctional childhood” and that those factors should be taken into account in sentencing.

Other court judgments from his convictions in the ACT justice system, where he spent several years, note that Denniss had been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder (a mental health condition that includes symptoms common to schizophrenia and mood disorders), antisocial personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, psychoactive substance-related disorders and mild intellectual disability.

Expert forensic psychiatrists appointed by the Coroners Court as part of the inquest said a review of Dennis’s history supports a diagnosis of ADHD, noting his tendency for impulsivity, but said there was no indication of hallucinations or psychosis at the time of his death.

One of the experts, Danny Sullivan, said it’s likely Denniss had antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder, in part because he appeared to have trouble regulating his emotions.

But Victoria Hovane, who has extensive knowledge of Aboriginal cultures and experiences of intergenerational trauma, said Denniss may have had complex post-traumatic stress disorder (cPTSD) and that many of his symptoms could be explained as a trauma response and a normal or adaptive way of responding to racism.

In reviewing the materials, she noted she was struck by the limited consideration of the extensive personal trauma he had experienced, let alone the potential impacts of intergenerational trauma.

Murphy, who attended every day of the inquest, says her brother entered the justice system in NSW at age 14 and struggled to get free.

In custody, he endured a lot of pain and I think sometimes he was acting up because of that.

“But he was the nicest person you’d ever meet.”

Denniss spent time in and out of jail, primarily on convictions for property offences such as theft, which were sometimes fuelled by alcohol and drug use.

His list of criminal convictions, accrued over a decade, grew to be substantial. A review of ACT court judgments shows judges believed they were left with little room for leniency, despite acknowledging his mental health conditions would “make his time in custody somewhat more burdensome than would otherwise be the case”.

Some noted that his mental health conditions also increased the likelihood of further offending and cited considerations for protecting the community.

Over time, Denniss’s behaviour in prison appeared to escalate, and towards the end of his life, his sentences significantly increased due to convictions for assaulting prison guards and setting fire to his cell on more than one occasion.

He would ultimately spend half of his life in custody.

‘Prone to self-harm’

The inquest heard that the more Denniss acted out, the tougher his conditions in prison became — and the more callous his treatment by prison authorities.

The last psychologist to treat Denniss before he died was a woman working at the Mid North Coast Correctional Centre in Kempsey, NSW.

She described him as being “prone to acts of self-harm”, and said there had been several incidents over the few months he was at the prison. Some acts were stopped before harm could be caused; in other instances, Denniss was given medical assistance afterwards.

Before he reentered the NSW correctional system, the Wiradjuri man had allegedly been the subject of a cruel hangman game, played by staff in the ACT Corrective Services on a staff whiteboard in 2018. A separate ACT inquiry is expected to take place.

An Aboriginal health care service in the ACT had apparently advocated for Denniss to be placed into a mental health facility at the time, but this never occurred.

Within a day of arriving at the Kempsey prison in early 2023, the psychologist said Denniss was self-harming and her focus was to stabilise him. She explained he was “not in the right space for ongoing therapy” because he was in a state of dysregulation or distress.

Family members of Tian Jarrah Denniss help to lower his coffin into the ground at his funeral in Wagga Wagga. Source: Supplied

Evidence suggests Denniss’s mental health may have been undermined by frequent transfers over the previous two years. He moved centres 17 times and experienced more than 100 cell moves.

The psychologist developed a behaviour management plan in consultation with Denniss and a summary of this was placed near his cell door, which included advice intended for guards on his triggers and how these should be managed.

Her observation was that Denniss struggled to accept when a reasonable request was delayed or denied, and this often precipitated violence. She advised staff to avoid direct confrontation, remind him of agreed-upon expectations and communicate calmly and clearly.

The inquest heard that Denniss could be demanding of custodial staff, although he did develop a rapport with some. The psychologist hypothesised this may be because staff were responsible for implementing his routine and would refuse to bend the rules.

She recalled sometimes entering the unit and seeing Denniss in an argument where he was elevated and yelling, at which point he would turn to her and say in a friendly tone: “Hello miss, how are ya?”

Even if he met you with anger or aggression, you had to keep that consistency and reassurance.

She noted that a non-threatening communication style would de-escalate the situation and calm him down.

Despite being in segregation, Denniss was described by his family as “outgoing” and social. It was noted that he requested contact with other inmates, and that one of the solutions implemented was to lock him in a telephone cage that was in a communal area of the centre, allowing him to talk to other inmates. He could also ring people, including his family.

The psychologist was never able to progress him off the management plan because he was transferred to Silverwater within months. She was not told about the move beforehand, but said she wasn’t sure if more time at the prison where she worked would have necessarily helped, as it was short-staffed and there was not enough stability at the time to benefit Denniss.

“The unit he was in was frequently changing custodial staff; he didn’t cope well with that,” she said, noting that he would not be allowed out of his cell when there weren’t enough staff on duty.

There were also different approaches among guards. Some would be open, would read the management plan and work well with Denniss, she said; others would say “this is how the unit is run, I’m in charge”.

When asked what might have been offered to help Denniss, she said stabilising his mental health enough to move him to a general wing and some kind of regular contact with an external psychologist would have assisted, although he would likely have had to find a way to pay for this.

“That would have allowed him to move forward.”

No continuity of care

Denniss’s relationship with the psychologist at Mid North Coast Correctional Centre was severed once he moved to Silverwater, after which he was managed by a risk intervention team made up of two Corrective Services staff (one with mental health training) and a member of Justice Health NSW, a healthcare provider for people in the criminal justice system.

Under questioning, senior Corrective Services NSW officials acknowledged the CPU did not offer any real therapeutic benefit to inmates in August 2023 and could instead be described as a form of warehousing for high-risk inmates.

Hovane says it’s difficult for any kind of mental health intervention to have the intended impact if the environment is not experienced as safe and stable.

If you’re not providing a stable environment and continuous care by people [they’ve] formed a therapeutic relationship with … [it] can undermine therapeutic efforts.

This is particularly important in Denniss’s case, explained the forensic psychiatrist, because Indigenous people tend to experience correctional facilities and other custodial settings as inherently unsafe, which is compounded by the innate power imbalance between prisoners and staff.

Hovane told the inquest the frequent moves may have affected his sense of safety and ability to establish relationships, which could have had a further destabilising impact on his wellbeing.

The frequent moves also meant Denniss’s family also didn’t get a chance to visit him.

During his time at Mid North Coast Correctional Centre, the psychologist noted she had little time to provide counselling as she spent much of her time writing assessments, and if inmates were transferred, it was impossible to provide continuity of care.

Even if Denniss had been able to stay at the facility, he would only have been entitled to six sessions with a psychologist, and they would have had to consult with senior experts before providing further assistance.

A break from boredom

According to forensic psychiatrist Danny Sullivan, some people engage in self-harm because they have restricted opportunities to voice their needs, not necessarily because they want to die.

Self-harm can start a negotiation and help them to get what they want — something they’ve previously asked for and been denied — whether that’s a chat, tea, fresh air or medication.

Of the seven self-inflicted Indigenous deaths in prison custody in 2023/24, only two have been recorded as intentional. The intent of the remaining five is still to be determined by the coroner.

Almost half the Indigenous prisoners who died in prison custody in 2023/24 died of hanging and related complications, compared with 23 per cent of non-Indigenous prisoners. Source: SBS News

Sullivan explained the importance of providing people with time outside, adding that it can serve as a break from a highly monotonous environment and help shift a person’s mindset. Eating can also offer relief from mental fatigue and boredom, as well as provide an opportunity to socialise.

Asked about the prison practice of serving inmates dinner around 2pm, which was noted as being due to staffing challenges, Sullivan said evidence suggests hunger could fuel behavioural disturbances.

Paradoxically, the more someone self-harms in prison — even if they are just wanting access to food or relief from boredom — the more restrictive their environment becomes. Privileges such as clothing, TV and bedding are typically taken away.

Sullivan said this can lead to an escalation of protest, anger or hopelessness.

‘No one opened the cell door’

Four officers were standing outside Denniss’ cell by 7.05pm, but they still didn’t open the door, even though at least one of them was starting to doubt whether Denniss was faking it.

Guards acknowledged it was possible to see Denniss slumped on the ground. But the first two on the scene – neither of whom speaks English as their first language – pointed to Denniss’s inmate management plan and a directive called “IAT movement only” as the reason they didn’t act sooner.

They say Denniss was a “challenging” inmate with a history of assaulting officers and they thought specialist officers — the Immediate Action Team (IAT) — needed to be present to open the door, not just in instances when Denniss needed to be relocated. This was disputed in the inquest by their seniors, and advice has reportedly since been circulated that officers must assist in medical emergencies if it’s safe to do so, even if they are alone.

The first officer was outside Denniss’s door for seven minutes before IAT members arrived and started first aid. A second officer arrived a minute after him.

The counsel assisting pointed out that the first two guards on the scene had not followed Denniss’s management plan in other regards, such as checking on him every half an hour.

“Why not break his plan to save his life?” she posed to one of them.

There’s a long pause before the officer answers “yes, ma’am”.

“Yes.”

The NSW Coroners Court in Lidcombe. Source: SBS News

The first guard on the scene, who had been swivelling around in his chair moments before, took 90 seconds to radio for medical help.

He made a tearful apology to Denniss’s family during the inquest, saying: “I’m sorry, I should have done better. I think I made a mistake in assessing the gravity of the seriousness of Tian Jarrah.”

A fellow inmate known as Witness A was located in a cell across from Denniss’s and told the inquest his life could have been saved, but the officers didn’t care.

He characterised the attitude among guards as racist, saying that he was viewed as “just another black c–t in jail”.

He says he wants the family to know that Denniss’s death was unnecessary.

“It was completely preventable.”

‘You expect your family members to come home’

In the inquest’s final days, counsel assisting confronted senior members of Corrective Services NSW with a long list of failings.

These include: the lack of handover from an earlier shift; staff being uninformed of inmate support plans; objects not being removed from cells that could be used for self-harm; physical observations not being done; knock-up calls being ignored; staff in two offices watching TV; the lack of a prompt cell check after a camera had been covered; and staff not entering a cell even though the situation was considered life threatening.

“I understand some of the officers have given evidence to the court that they could have done more and they should have done more, and I agree we should have done more,” he said.

The coroner will hand down her report at a later date, but in the meantime, Denniss’s family are holding out hope that the inquest will lead to change.

Dennis’s sister Iesha says she worries for her two other brothers, who are also in jail at present.

“You never know if they’re going to come home,” she tells SBS News.

“You expect your family members to come home from jail, but Tian Jarrah never made it home.”

If you or someone you know needs help contact: l Lifeline 13 11 14, text 0477 13 11 14, visit lifeline.org.au; Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander crisis support line 13YARN on 13 92 76; Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800 kidshelpline.com.au; Mensline Australia 1300 78 99 78 mensline.org.au